About AD 98, slightly more than a century after Strabo wrote his Geographica, historian Publius Cornelius Tacitus published Germania, one of the classical world's best-known ethnographic works. Germania's final chapter covers tribes living to the Germans' northeast — the Peucini, Veneti, and Fenni. This last group (whose name bears an obvious similarity to the exonym "Finn"), Tacitus considers uniquely barbaric. His (brief) description may be the earliest account of Uralic (1) construction methods:

The Fenni are strangely beast-like and squalidly poor; neither arms nor homes have they; their food is herbs, their clothing skins, their bed the earth. . . . The little children have no shelter from wild beasts and storms but a covering of interlaced boughs. Such are the homes of the young, such the resting place of the old. (2)At a glance, the text seems to support my contention. But, as usual, the Latin is too vague to reveal much about its subject. The relevant line, "ramorum nexu contegantur," could be translated as "a covering of interlaced boughs," but it might also mean "a roof of connected branches" or "a shelter of fastened twigs." Then again, had Tacitus intended to describe log houses, he surely would've employed truncus or trabes, the two Latin words often applied to trunks and timbers.

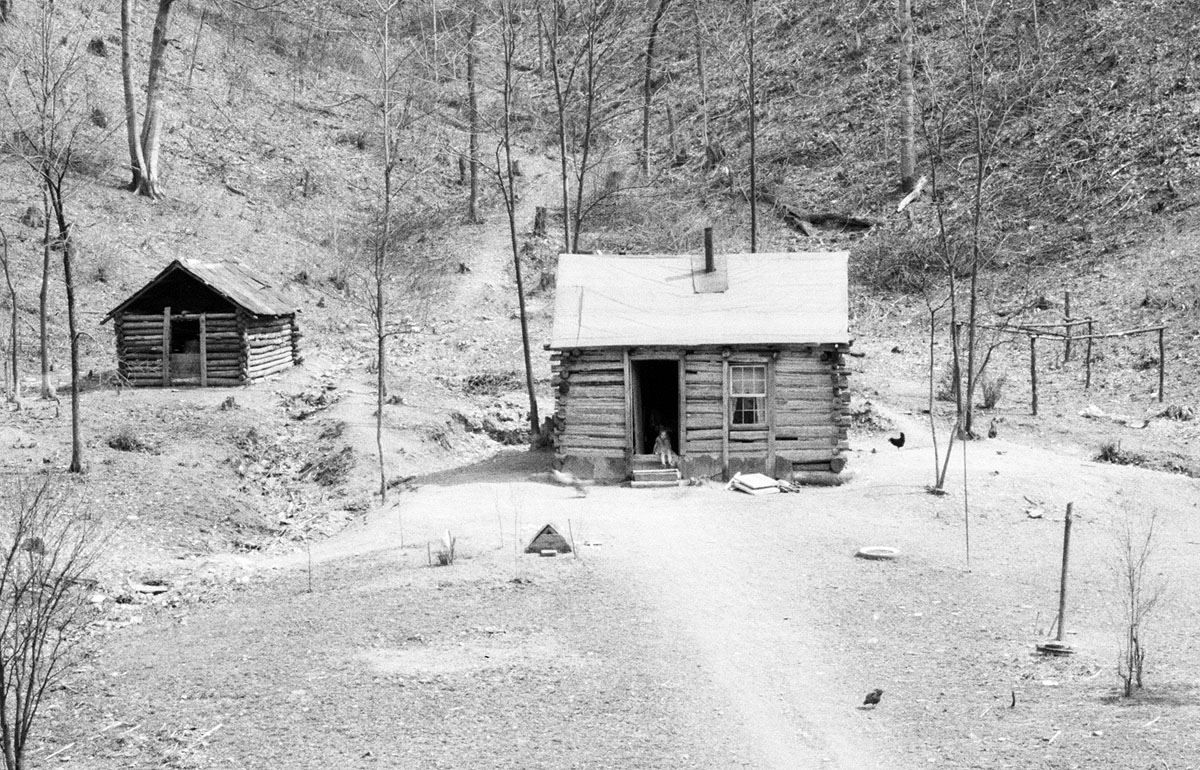

It's likely, then, that the Finns adopted log construction well after the first and second centuries AD. But who (if anyone) introduced the practice to them? When did the shift from branch hovels to log houses occur? Alas, I can't say. No doubt, the westernmost Uralic-speaking populations interacted with southern Scandinavia's Germanic peoples, who preferred to build timber long-houses (a practice which survived into the Viking Age). The pastoral Sami constructed tents and pole (or earthen) huts — goahti — into the twentieth century. In some ways, these habitations resemble the "covering of interlaced boughs" described by Tacitus.

|

| A Sami family outside their goahti. Photo, 1870s, from the Galerie Bassenge collection; taken from Wikipedia. |

Whatever its origin, log architecture had, by the early modern period, become entrenched in Scandinavia and northwestern Russia. Log dwellings, storehouses, barns, and (especially) saunas dotted the Finnish landscape, and peculiarities of construction acquired distinctive names — hammasnurkka, lukko, and whatnot. At Helsinki's Seurasaari Museum, 87 buildings, the majority log, testify to the popularity of timber construction.

|

| The Niemelä stable, now housed at the Seurasaari Museum. Photo by Jani Patokallio, 2009, from Wikimedia Commons. |

In the seventeenth century, Swedes, Norwegians, and Finns brought their architectural traditions to North America, and thus (in conjunction with the Germans) engendered the practice which defined frontier architecture in the United States.

1) I've assumed, of course, that Tacitus's Fenni were, in fact, the ancestors of today's Finns, Estonians, Livonians, Karelians, Ingrians, and Vepsians. But such an identification is a matter of controversy.

2) From the Church, Brodribb, and Cerrato translation (1942); transcribed by Perseus.