whimsy : a playful or amusing quality : a sense of humor or playfulness (1)Now, I'll let Samuel Johnson and Webster's Collegiate Dictionary define "whimsy":

Whi'msey. n.s. [Only another form of the word whim.] A freak; a caprice; an odd fancy; a whim. (2)

whim'sey, whim'sy (hwīm'zī), n.; pl. . . . A whim; freak; caprice. (3)

Two (or one-and-a-half) definitions separated by 161 years, yet scarcely a change between them. Only during the twentieth century, it seems, did "whimsy" gain its now-standard meaning as a species of humor. For Johnson and the Webster's editors (who seem simply to have borrowed Johnson's definition), absurdity alone constituted whimsy. Indeed, a tragedy could be whimsical, so long as that tragedy involved the inexplicable. Thus, the nineteenth-century man might stumble into whimsy in a way we now cannot (whimsy having since become a form of comedy). Comedy — the art of the absurd — presupposes intention; the accidentally absurd is merely absurd. We may laugh at it, but we needn't dub it comedy.

I'm justified, then, in calling particular structures "whimsical," because I employ the term in its original sense. Plenty of bizarre, fanciful, and arbitrarily designed buildings dot the American countryside. The carpenters who erected these oddities didn't intend to produce humorous works, of course. But they deviated from convention, and they thereby cursed their creations to notoriety.

In Hillsdale, Michigan, stands a frame house adorned with ample Classical Revival ornamentation: cornice brackets, dentils, an attic lunette, two tripartite windows (one Palladian in form), and a grand trabeated entrance. That the dwelling draws inspiration from classical modes is not odd; other Hillsdale homes (such as Frederick Stock's) do, too. Rather, its peculiarity lies in its proportions. The humble "upright-and-wing" form underlying the ornamentation is hardly fitting for neoclassical grandeur. In no way is the result unattractive, but it does tempt passersby to chuckle.

The spoked brackets embellishing the Abram Fisk House — which stands near Coldwater, Michigan, about half an hour west of Hillsdale — resemble either flower petals, wagon wheels, or fan blades. (Architectural Rorschach tests are always a delight.)

An Italianate house — nay, mansion — in South Charleston, Ohio, features lintels incised with snowflakes. (How apropos, then, that I happened to photograph it during the winter.)

One Bartlow Township, Henry County barn — known locally as the "Chinese barn" for its pagoda-like appearance — fit my definition of "whimsical." Commissioned by George Hyslop in 1910, the building, alas, collapsed in 1984. The September 1, 1916 issue of Hoard's Dairyman published an article (penned by Hyslop himself) about the barn, touting it as "stall-less." Hyslop's tower-adorned home also rose to the level of whimsy, but, like his barn, disappeared in the 1980s.

The apogee of American architectural whimsy may be Orson Squire Fowler's octagonal house. Fowler (1809–1887), a phrenologist and reformer by trade, recommended that his countrymen "apply [nature's] forms to houses" (4) and erect octagon-shaped abodes "more consonant with the predominant or governing form of Nature — the spherical" (5). Of Ohio's 55 known (historic) octagonal buildings, the Gregg-Crites House, in Pickaway County, is among the finest.

I'm justified, then, in calling particular structures "whimsical," because I employ the term in its original sense. Plenty of bizarre, fanciful, and arbitrarily designed buildings dot the American countryside. The carpenters who erected these oddities didn't intend to produce humorous works, of course. But they deviated from convention, and they thereby cursed their creations to notoriety.

In Hillsdale, Michigan, stands a frame house adorned with ample Classical Revival ornamentation: cornice brackets, dentils, an attic lunette, two tripartite windows (one Palladian in form), and a grand trabeated entrance. That the dwelling draws inspiration from classical modes is not odd; other Hillsdale homes (such as Frederick Stock's) do, too. Rather, its peculiarity lies in its proportions. The humble "upright-and-wing" form underlying the ornamentation is hardly fitting for neoclassical grandeur. In no way is the result unattractive, but it does tempt passersby to chuckle.

|

| Classical Revival cottage, circa 1900; Hillsdale, Michigan. |

The spoked brackets embellishing the Abram Fisk House — which stands near Coldwater, Michigan, about half an hour west of Hillsdale — resemble either flower petals, wagon wheels, or fan blades. (Architectural Rorschach tests are always a delight.)

|

| Abram Fisk House (NRHP-listed), circa 1863; Coldwater Township, Branch County, Michigan. |

An Italianate house — nay, mansion — in South Charleston, Ohio, features lintels incised with snowflakes. (How apropos, then, that I happened to photograph it during the winter.)

|

| John Rankin House, 1885; South Charleston, Ohio. |

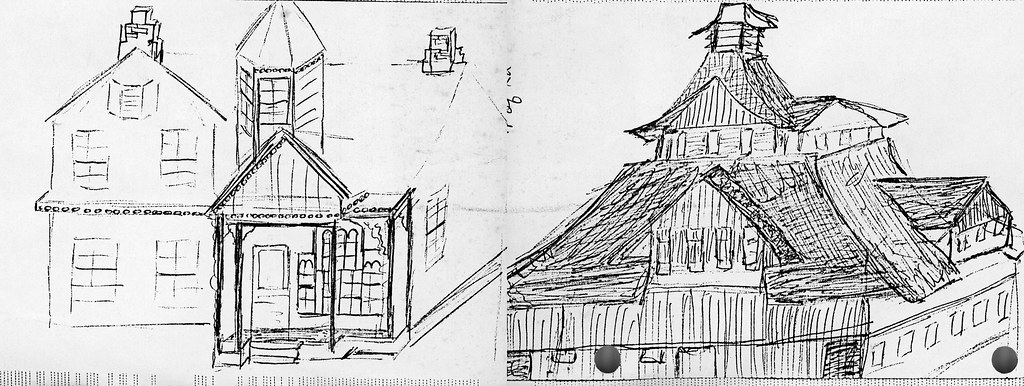

One Bartlow Township, Henry County barn — known locally as the "Chinese barn" for its pagoda-like appearance — fit my definition of "whimsical." Commissioned by George Hyslop in 1910, the building, alas, collapsed in 1984. The September 1, 1916 issue of Hoard's Dairyman published an article (penned by Hyslop himself) about the barn, touting it as "stall-less." Hyslop's tower-adorned home also rose to the level of whimsy, but, like his barn, disappeared in the 1980s.

|

| George Hyslop residence and barn; Bartlow Township, Henry County, Ohio. Sketch by Mrs. Harry Heinzerling, 1979, from the Donald Hutslar collection; used courtesy of Jean Hutslar. |

The apogee of American architectural whimsy may be Orson Squire Fowler's octagonal house. Fowler (1809–1887), a phrenologist and reformer by trade, recommended that his countrymen "apply [nature's] forms to houses" (4) and erect octagon-shaped abodes "more consonant with the predominant or governing form of Nature — the spherical" (5). Of Ohio's 55 known (historic) octagonal buildings, the Gregg-Crites House, in Pickaway County, is among the finest.

|

| Gregg-Crites House, 1855 or 1856; Circleville Township, Pickaway County, Ohio. |

Such buildings may amuse us. Evidently, the architectural historians of another era reacted similarly. In Early Homes of Ohio, Frary writes:

Along with the fine craftsmanship that exists in so much of Ohio's early architecture are to be found many examples of design in which the attempts of untrained mechanics to interpret half-understood drawings verge closely on the ludicrous or the pathetic. On the other hand these interpretations often command our admiration, revealing as they do rare ingenuity in solving problems of construction, and active imagination in working out details of design with which the builders were unfamiliar.

. . .

The clumsy attempts at classic pillars, columns, moldings, and cornices often produced curious effects that would scarcely pass muster in a school of architecture or a Beaux-Arts competition. They were crude, the details often painfully misunderstood, yet in them we recognize a sincerity that wins our admiration. Those pioneer builders were creating a vernacular in architecture possessing vitality and spontaneity that is often missing in highly sophisticated creations. We may smile at the clumsy results, but we must admire the simple but direct thinking which they represent. (6)We, too, smile at those buildings "clumsy" by Greco-Roman standards, but we've lost the ability to recognize them as such. But this is a subject for another post.

3) Webster's Collegiate Dictionary (1916), 1,090.

4) O.S. Fowler, A Home for All; or, the Gravel Wall and Octagon Mode of Building (1854), 82.

5) Ibid., 88.

6) I.T. Frary, Early Homes of Ohio (1936), 215.

4) O.S. Fowler, A Home for All; or, the Gravel Wall and Octagon Mode of Building (1854), 82.

5) Ibid., 88.

6) I.T. Frary, Early Homes of Ohio (1936), 215.

No comments:

Post a Comment