By mid-century, Ohio's counties — or, at least, its well-populated counties — had largely acquired the ample road systems which survive today. (The frequency with which Greek Revival-era dwellings — even those fronting minor thoroughfares — align with roads is evidence of this.)

|

| Inter-County Highway 124 (now State Route 28), a superlative dirt road. Photo from the ODOT archives. The background home is extant. |

Until the twentieth century, the Ohio traveler could expect little in the way of comfort. Indeed, a few wealthier counties had, in the preceding century, gravelled or macadamized their roads, but the balance of the state's routes were, by all accounts, veritable styes. In American Notes, Charles Dickens (yes, that Charles Dickens) quips about an 1842 stagecoach ride from Columbus to Sandusky:

It was well for us, that we were in this humour, for the road we went over that day, was certainly enough to have shaken tempers that were not resolutely at Set Fair, down to some inches below Stormy. At one time we were all flung together in a heap at the bottom of the coach, and at another we were crushing our heads against the roof. Now, one side was down deep in the mire, and we were holding on to the other. Now, the coach was lying on the tails of the two wheelers; and now it was rearing up in the air, in a frantic state, with all four horses standing on the top of an insurmountable eminence, looking coolly back at it . . . (1)

|

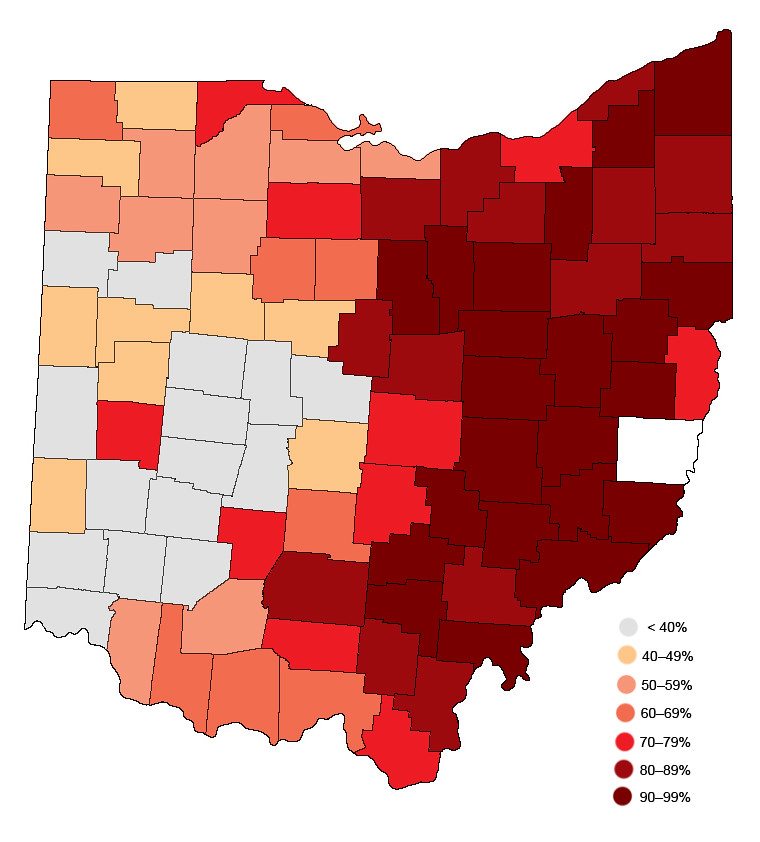

| Earth-surfaced (i.e., dirt) roads in Ohio, 1915. Data sourced from Names and Numbers of Inter-County Highways and Main Market Routes, and Highway Statistics of Each County, published by the Ohio Highway Department. The darker the county's coloring, the greater its percentage of dirt roads. (Belmont County is clearly an anomaly.) |

Navigational Nomenclature

In the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, the state's county- and township-maintained routes lacked formal names. Open any Victorian-era property atlas, or glance at any prewar county highway map: the local roads are bound to be anonymous. Only after World War II, I suspect, did township and county governments bother to name their vast road networks. (More than likely, this mass-christening coincided with the widespread paving of minor thoroughfares, which had hitherto been largely earth-surfaced.)

Many of Ohio's rural roads bear "connective" names designating the communities which lie at their termini, or else describe the property owners whose tracts sat at their ends. Rosedale-Plain City Road, in northern Madison County, joins unincorporated Rosedale and more metropolitan Plain City, naturally. To the south, Pancake-Selsor Road honors members of the Pancake and Selsor families, prominent in southern Madison County. Rarely do given names appear in road labels. Adams County contains a few exceptions: Starley Gustin Road (which traverses fertile bottomland bordering Ohio Brush Creek), Ira Gustin Road (in Bratton Township), and George C. Biely Road, among others. Many more road names are sourced from natural features, as the repetition of "Hollow," "Valley," and "Run" — in Ohio's Appalachian counties — attests.

All Ohio counties assign numbers to their thoroughfares, but a few (clustered mostly in the state's northwestern quadrant) lack true, or nominal, titles. Williams County, bordering Indiana and Michigan, uses a hybrid numeric-alphabetic system, with its north-to-south-running routes receiving a number (1 through 24), and its east-to-west-traveling roads receiving a letter (A through S). The many routes that deviate by splitting sections combine letters and numbers. Thus, near Montpelier is County Road K-50 (a longitudinal byway situated equidistant from County Road K and County Road L). Logan County's numbering, on the other hand, appears to be inexplicable.

Carroll County's traffic engineers seemingly selected its roads' names by flinging darts at a board or, perhaps, choosing dictionary entries at random. Bacon Road begins at Arrow Road; intersects Glacier, Glory, Jasmine, Buck, Gallo, Fisherman, and Trump; and terminates at a state highway. Elsewhere, Aurora meets Apollo, and Nassau encounters Nature. Confusingly, Lemon Road lies a few miles distant from Lumen Road. Andora Road commemorates — in misspelled form — the tiny Pyrenean nation of Andorra (or Andora, Italy), while Ming Road may memorialize the long-lived Chinese dynasty.

Other oddities surely exist, scattered across Ohio's 44,825 square miles.

1) American Notes for General Circulation, Volume II (1842), 162.

No comments:

Post a Comment