This farmhouse doesn't seem particularly noteworthy at first glance. I encountered the property owner (?), who seemed neither hostile nor thrilled about my trespass. Not wanting to overstay my welcome, I captured only a few photographs.

While the one-and-a-half-story front ell is quite featureless, the rear section is constructed of brick, with segmental arched windows at the basement level. I first assumed that the brick portion was built prior to the frame section; an incorrect assumption, as it turns out.

| West facade. The tarp covers an arched basement-level window. |

| Porch area. Note the row of vertical bricks, barely visible between the porch floor and door. |

A few months ago, I discovered an identical house merely a half-mile away.

|

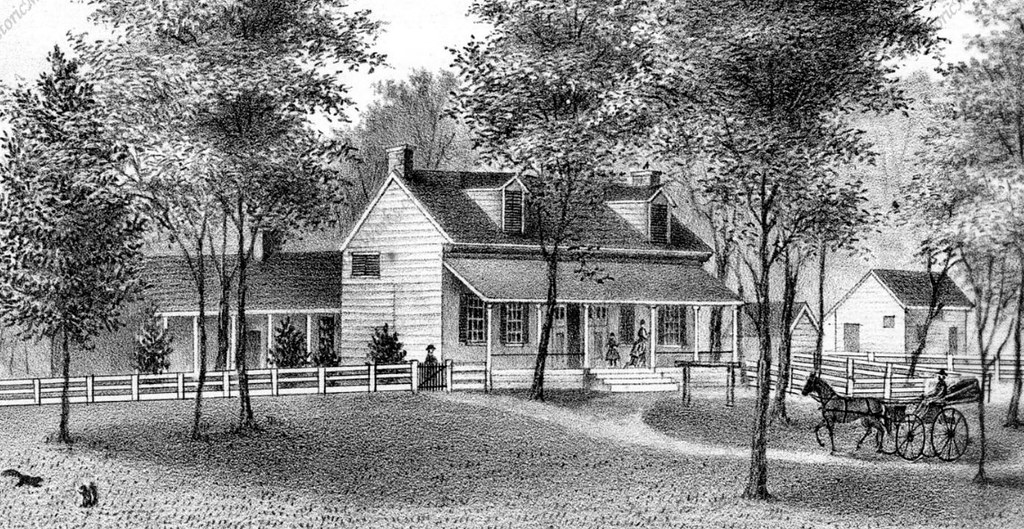

| The twin house, thankfully inhabited. Photo (circa 2001?) is from the Union County Auditor's website. |

The northern section of Darby Township contains a number of brick farmhouses, part of a German settlement area centered around nearby St. John's Lutheran Church.