One of these decades, I'll summon the energy to write a book about Ohio's cultural landscape — something akin to the excellent Roadside Geology series, but for buildings. It'll no doubt contain a county-by-county discussion of architectural trends. Such chapters will probably resemble this blog post.

Organized in summer 1797 and named for the sitting U.S. president, Adams is Ohio’s third-oldest county — and its cultural landscape betrays the fact. It is, in its natural geography, a place of variety. From west to east, the clayey and mildly broken landscape gives way to thin-soiled knobs (north of West Union), cliff-rimmed plateaus, the deep valley of Brush Creek, and the most rugged portion of Appalachian Ohio. To the south flows the Ohio River, whose fertile bottomlands supported Adams County’s earliest settlements. In the southwest, near Bentonville and in Sprigg Township, limestone outcroppings dot the rolling, sinkhole-pockmarked countryside — a rare region of

karst topography and part of a small incursion of the Bluegrass into the Buckeye State.

|

| Adams County Courthouse, 1911; West Union. |

Historically, Adams County’s agricultural situation varied as much as its landscape. One early Ohio gazetteer notes that “[t]he land . . . embraces a variety of soils, from the best to the worst.” This is plainly true. Into the latter category falls the valley of the Ohio River — relatively narrow except near Sandy Springs, at Adams County’s southeastern corner. The passably fertile land surrounding Cherry Fork, Winchester, and Seaman, in the west, supported the crops common to southern Ohio. Throughout the county, pasture was (and is) common. As in nearby Brown and Clermont counties, tobacco cultivation flourished after the Civil War — particularly in the narrow eastern stream valleys, which remained sparsely populated until the nineteenth century’s closing decades.

European settlement began in Adams County well before the subdivision received its name. In 1790, Nathaniel Massie (1763–1813), a Virginia-born surveyor, crossed the Ohio River near the mouth of Isaac’s Creek and established an outpost, known first as

Massie’s Station and soon rechristened

Manchester. With Massie came a contingent of settlers — the first legal residents of the Virginia Military District, in which Adams County wholly lies. Not until the Treaty of Greenville (1795), though, could settlers live without fear of Native American retaliation. Between 1790 and 1795, several Manchesterites — including members of the Ellison and Edgington families — were either attacked or captured by local tribes. In the ensuing decade, Europeans trickled into the area, mostly establishing subsistence farms in the valleys of the Ohio River and Brush Creek. In 1796 and 1797, Colonel Ebenezer Zane cut the eponymous Zane’s Trace through the soon-to-be county from northeast to southwest. About this time, when the Northwest Territory’s legislature decided to establish Adams County, it selected Manchester, naturally, as the seat of government.

This decision proved fractious. Within a year, and after much bickering, the county commissioners had uprooted and repositioned themselves twice — first from Manchester to Adamsville, a comparatively remote site on the banks of Brush Creek; and thence to a two-story log courthouse in Washington, a nascent Ohio River community. In 1804, the Adams County government moved yet again, this time to West Union, a newly platted village perched on a hilltop several miles inland. For once, the choice stuck. Adamsville and Washington faded to nonexistence, while West Union prospered. By 1810, 229 souls called the community home. Future Kentucky governor Thomas Metcalfe (1780–1855), a mason by trade, built a new courthouse — a two-story stone structure of almost residential appearance, with exterior chimneys and a round-arched Federal-style entry — in 1811. West Union’s rapid growth and mid-century stagnation (its population remained almost unchanged between 1830 and 1870) left behind a well-preserved early townscape — one rich in Federal-era commercial buildings and residences, and even a smattering of log structures. Since the 1960s, though, waves of remodeling and demolition have robbed the village of most of these buildings.

As West Union’s fortunes declined, Manchester’s rose — thanks to its riverside siting, which allowed it to become a shipping point for tobacco and other agricultural goods — and its population leaped from scarcely 400 (at mid-century) to nearly 1,000 (two decades later). The 1900 census recorded a population of 2,003. Thereafter, the village’s economy suffered. Both demolition and repeated flooding have left Manchester’s cultural landscape pockmarked, with mobile homes and vacant lots in lieu of a historic housing stock. Other sizable Adams County communities — including Winchester, Seaman, and Peebles — owe their economies, if not their existence, to the Norfolk and Western Railway, which was constructed in the 1870s. Smaller communities, some unplatted, dot the Adams County landscape.

At least two distinct migration waves peopled Adams County. The first occurred between 1797 and 1820; the second spanned the 1840s. In both cases, the waves brought a relatively homogenous contingent of settlers, predominantly Presbyterians of Scots–Irish descent. The majority came from Pennsylvania (both the southeast and southwest) and northwestern Virginia, and a sizable minority immigrated directly from Northern Ireland. A few Kentuckians spilled across the Ohio River into the southern townships, and a smaller number of Germans scattered themselves across the county. In the 1870s and 1880s, a third, mostly internal migration occurred; inhabitants of southern Clermont County and Brown County, Ohio — where burley tobacco had become a staple crop — flooded into the mountain hollows surrounding Blue Creek and Wamsley, in Jefferson Township. The Adams County settlement landscape is not as diverse as those of other Ohio counties. In general, Virginians tended to dominate in the north, whereas Pennsylvanians and Kentuckians formed a majority in the south. By the end of the nineteenth century, foreign-born Scots–Irish populations were confined mostly to pockets around West Union and in Monroe Township.

Adams County retains an unusual number of early buildings — perhaps an unsurprising fact, given that it functioned as a locus of settlement during the territorial period. For the most part, these structures make use of common vernacular forms. On the banks of Brush Creek, not far from the Zane’s Trace right-of-way, stands a single-pen log house reportedly built by Peter Shoemaker (d. 1804 or 1809), who settled in Meigs Township in 1796. In appearance, the house is standard — one-and-a-half stories in height, three bays in width, and adorned only with an external brick chimney. A two-story braced-frame addition, built at an early date by a member of the Sproull family, significantly enlarges the building. Though evidence for the claim is circumstantial, Shoemaker’s home

may be Adams County’s oldest surviving residence.

|

| Shoemaker–Sproull House, circa 1796 (?); Meigs Township. |

Another surviving eighteenth-century log structure is the National Register-listed Treber Inn, built by John Treber, a Pennsylvanian, along Zane’s Trace in 1798. The single-pen building — notable for both its two-story front porch (perhaps original) and its rear stone addition, appended about 1810 — functioned as a tavern for much of the nineteenth century. Thankfully, it remains more-or-less unaltered, preserved in almost museum-esque fashion by its present owners.

|

| Treber Inn, 1798; Tiffin Township. |

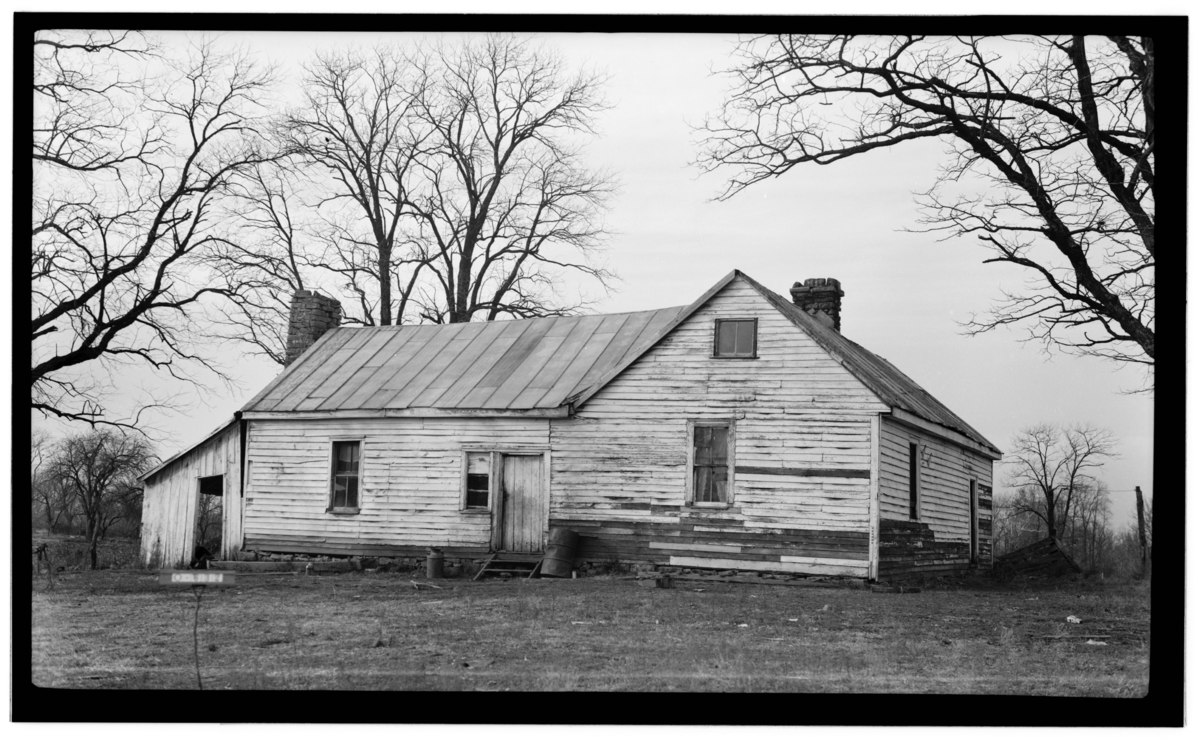

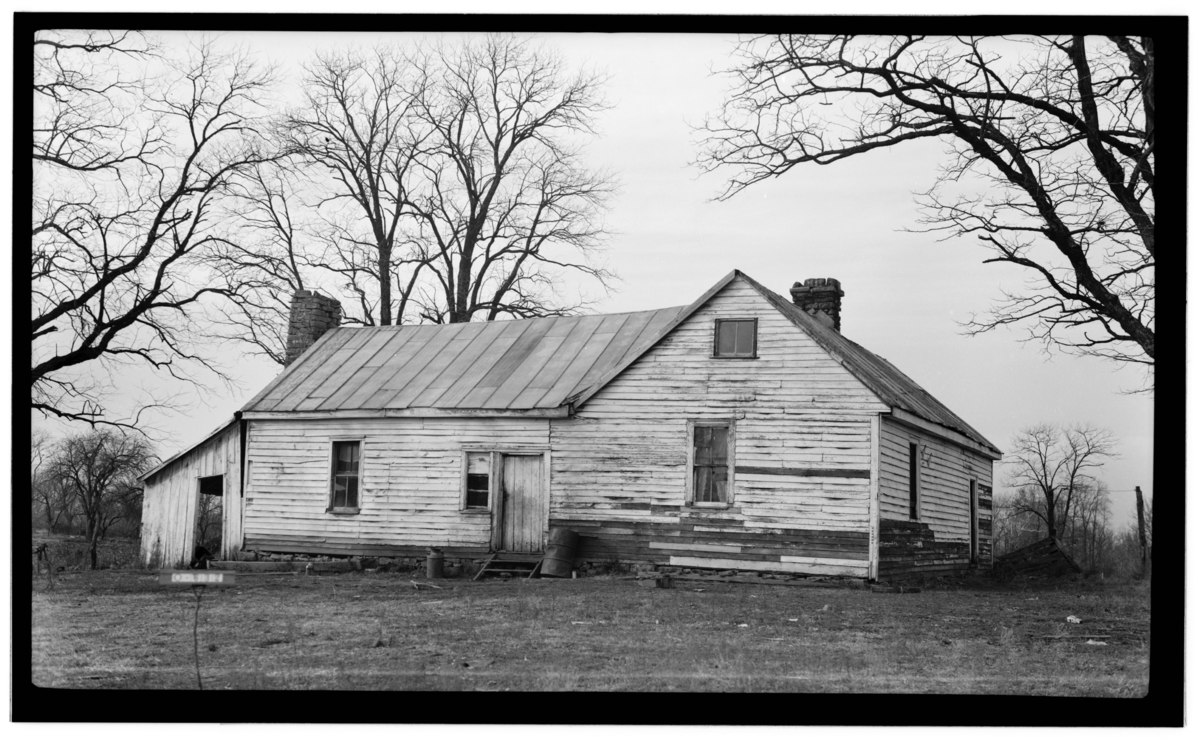

More typologically distinct was Buckeye Station, a residence surveyor Nathaniel Massie erected on a Monroe Township bluff in 1797. The house was a one-story, two-bay braced-frame structure of L-shaped plan, its front section divided by a massive central chimney — possibly an early variant of the “saddlebag” plan. A second stone chimney, placed on the exterior, accompanied the kitchen wing. What little interior ornamentation Massie’s abode boasted disappeared during its long life as a tenant house, but the exterior remained almost unchanged. The building’s eaves may have employed a system of framing more common to the eastern seaboard than to Ohio. Alas, a half-century of neglect has reduced Buckeye Station to little more than a pile of moldering boards punctured by a pair of stone chimneys.

|

| Nathaniel Massie House (Buckeye Station), 1797; Monroe Township. Photo by E.F. Schrand and A.R. Arend, 1936, from the Historic American Buildings Survey collection. |

Adams County retains several early limestone dwellings. The oldest among these is no doubt the 1798 Andrew Ellison House, which stands in a narrow hollow northeast of West Union and scarcely a mile from Zane’s Trace. Ellison, born in County Tyrone, Ireland, was among the early residents of Manchester. With its single-pen form, wide-based exterior chimneys, and primitive appearance, the one-and-a-half-story home betrays its pre-statehood origin. Its low-pitched roof and relatively lengthy side walls give it an appearance like that of other stone dwellings in nearby northern Kentucky —

evidence of a regional trend, perhaps. A slightly smaller, slightly later (1805) stone farmhouse stands in Liberty Township on land homesteaded by Thomas Kirker (1760–1837), another Tyrone native who later served as Ohio’s second governor. Like the Ellison House, Kirker’s residence is of essentially hall-and-parlor plan, albeit with a central (rather than a gable-end) chimney. In the 1850s, Kirker’s descendants enlarged the home with a two-story frame addition of “I-house” form. Two other Adams County stone homes survived into recent decades — a small, single-pen farmhouse in Scott Township, and a two-story stone-and-frame tavern built by one Isaac Aerl before 1810, just north of Peebles. Aerl’s tavern is noteworthy for its crude Flemish-bond stonework.

|

| Andrew Ellison House, 1798; Tiffin Township. |

|

| Isaac Aerl House, circa 1809; Meigs Township. |

Because of Adams County’s

isolation and relative poverty, log construction remained popular in the area

well into the nineteenth century. (Indeed, a few log homes date from the twentieth century.) By far, the majority

of the county’s surviving log buildings are one-and-a-half- and two-story

single-pen residences; double-pen structures and outbuildings are considerably

rarer. If preliminary surveys are any indication, the number of log homes

surviving in Adams County exceeds 100. A WPA survey of farm residences,

conducted in 1934, located 250 log homes — about 11 percent of Adams County’s

total. No features distinguish the county’s log houses, in general, from those

elsewhere, but overhanging plates and exterior chimneys seem to have been common.

One double-pen home of “saddlebag” form, exceedingly rare in Ohio, stands in

Sprigg Township. Another double-pen farmhouse once sat north of West Union, in Tiffin

Township. Though its configuration — two one-and-a-half-story pens separated by a

wide stair hall — suggested an early construction date, the building’s placement

in an agriculturally marginal area makes this conjecture less likely. Whatever

its origin, the house was a stellar example of early-nineteenth-century construction

practices, with interior and exterior chimneys, rake boards, wide clapboard

siding, and an integral rear porch tucked between enclosed corner rooms. This

building, owned in the 1880s by a member of the Cluxton family, survived into

the mid-1990s.

|

| Daniel Collier House, 1802; Tiffin Township. Razed. Photo by Rita or Leland Puttcamp, from Historic Landmarks in Ohio: Volume III, compiled by several chapters of the United States Daughters of 1812 in 1955. |

|

| Cluxton Log House; Tiffin Township. Razed. Photo by Stephen Kelley, 1977, from the collection of Donald and Jean Hutslar. |

Like other Ohio River counties, Adams County contains a few examples of plank construction—an uncommon variant of the usual notched-log system which uses narrow, sawed boards instead of hewed timbers. In two cases, such plank structures were mere additions to more traditional log houses. In another case, notched planks constituted the entire single-pen home. Only one of these three buildings remains standing — on U.S. Highway 52, just southwest of Manchester.

As is the case elsewhere in Appalachia, wood is, by far, the most common construction material among Adams County structures. Some homes use hewed logs; at least one, round logs. Most surviving pre-World War II residences, though, employ one of the two systems of framing common in America — braced framing, with its mortise-and-tenon joinery; and balloon framing, which reached Adams County after the Civil War. The county retains fewer than half a dozen stone structures, all ancient by state standards. Brick buildings — mostly built between the 1820s and 1850s — tend to cluster in the northwest (around Seaman), and in the upland valley which shelters Peebles. The county’s oldest brick structure, the 1801 Wickerham Inn — a low two-story, three-bay Flemish-bond structure, slightly altered — stands along the old Zane’s Trace between Peebles and Locust Grove.

|

| Wickerham Inn, 1801; Franklin Township. Photo from Wikimedia Commons, courtesy of Nyttend. |

Typologically, Adams County’s buildings fall firmly into the architectural tradition of the greater Upper South. Single-pen and hall-and-parlor homes, typically one-and-a-half stories in height, abound. Two-story residences of linear plan — so-called “I-houses” — constitute more than a third of the county’s surviving farm dwellings. Also common are one-and-a-half-story, double-pile homes of a type seemingly common to areas settled by the Scots–Irish. These buildings often consist of four rooms arranged around a central hallway, with chimneys (generally four, and sometimes two) placed at the periphery. The upper half-story invariably lacks a knee wall. Such homes, it seems, were constructed in great numbers about the time of the Civil War, and many feature (or featured) simplified Gothic Revival ornamentation — centered gables, lancet-arched windows, and bargeboards. In a few cases, the gable is front-facing. Of the homes depicted in Caldwell’s 1880 Illustrated Historical Atlas of Adams County, Ohio, more than a dozen fall into this category. Common late-nineteenth-century building-types also make an appearance — “gabled ell” cottages, cube-shaped dwellings, and whatnot.

Few Adams County homes merit stylistic classification. Ornamentation tends to be vernacular, and not high-style, in nature. Among frame buildings, clapboard siding and simple frieze boards are omnipresent. The Federal mode, for the most part, is evident only in interior woodwork and the occasional use of Flemish-bond masonry. Nods to the later Greek Revival style are only slightly more common. In Bratton Township, not far from the Highland County border, stands a five-bay frame “I-house” marked by a pedimented two-story porch with paired columns. Identical doorways, each surrounded by sidelights and a transom, open onto both of this porch’s levels. Members of the Gore family, who built the dwelling, hailed from northern Virginia, where such porches are commonplace. Similar porches adorn farmhouses in the townships of Bratton, Franklin, Green, Scott, and Tiffin. Also taking its inspiration from ancient Hellas is Liberty Township’s Gibboney House, a one-story, four-bay, L-shaped frame cottage with a pedimented porch and sidelight-flanked doorway.

|

| Gore House, circa 1845; Bratton Township. |

|

| Gibboney House, circa 1850; Liberty Township. |

By far, the most inventive of rural Adams County’s abodes is the Oliver Tompkins House — known informally as the “Counterfeit House” — in Monroe Township. A counterfeiter by trade, Tompkins purchased a farm on Gift Ridge (not far from Buckeye Station) in 1840, then erected a home designed to conceal his moneymaking operation. In form, the structure is unique enough. It employs the usual center-hall plan, but its roof is hipped (rather than gabled), and its windows are framed by paneling and wide, crossette-endowed trim. The chimneys’ stacks are turned 45 degrees from the perpendicular, and the central hallway terminates at a recessed, trabeated doorway (with sidelights and a transom). Tompkins outfitted his home with features intended to hide his scheme: deceptively locked doorknobs, a slot where patrons could insert cash, and a concealed second-floor room where the actual counterfeiting occurred. For decades, the Tompkins House doubled as a private residence and an impromptu museum. But now, alas, the building stands abandoned, overgrown, and tornado-damaged.

|

| Oliver Tompkins House ("Counterfeit House"), 1840; Monroe Township. Photo from Wikimedia Commons, courtesy of Aesopposea. |

Outside West Union and Manchester, high-style Italianate structures are as rare as Greek Revival ones. A few Adams County builders applied minor Italianate detailing — bracketed cornices and hip roofs, usually — to the common “I-house” form. One farmhouse, built by the Grimes family amid Ohio River bottomland (not far from the site of Washington), managed to capture the irregularity that typifies the Italianate mode. This home, built of brick and restrained in its ornamentation, disappeared during construction of the Killen Generating Station. For the most part, the Italianate (and the Gothic) made an appearance only at the periphery — in minor details and porches, which often featured scrollwork, spandrels, and brackets.

|

| Italianate farmhouse, circa 1885; Scott Township. |

In rural Adams County, at least, most late-nineteenth-century homes are firmly astylistic. Elements associated with the greater “folk Victorian” vocabulary — exterior strapwork and shingling, stylized window trim, bargeboards and gable-end trusses, and spindlework—appear occasionally and in small numbers. A vacant balloon-frame farmhouse on State Route 136, in Liberty Township, employs most of these tropes. After about 1900, residual classical ornamentation again gained popularity. Nonetheless, the overwhelming majority of notable Adams County buildings date from the nineteenth — and not the twentieth—century.

|

| Abandoned farmhouse, circa 1890s; Liberty Township. |