|

| Siegfried's tavern in 2008. (Yes, this photo is terrible; but then, a person trapped in a moving vehicle cannot expect compositional brilliance!) |

|

| And, Siegfried's tavern before its abandonment. Photo by George Cryder (?), 1969, from the Delaware County Historical Society collection. |

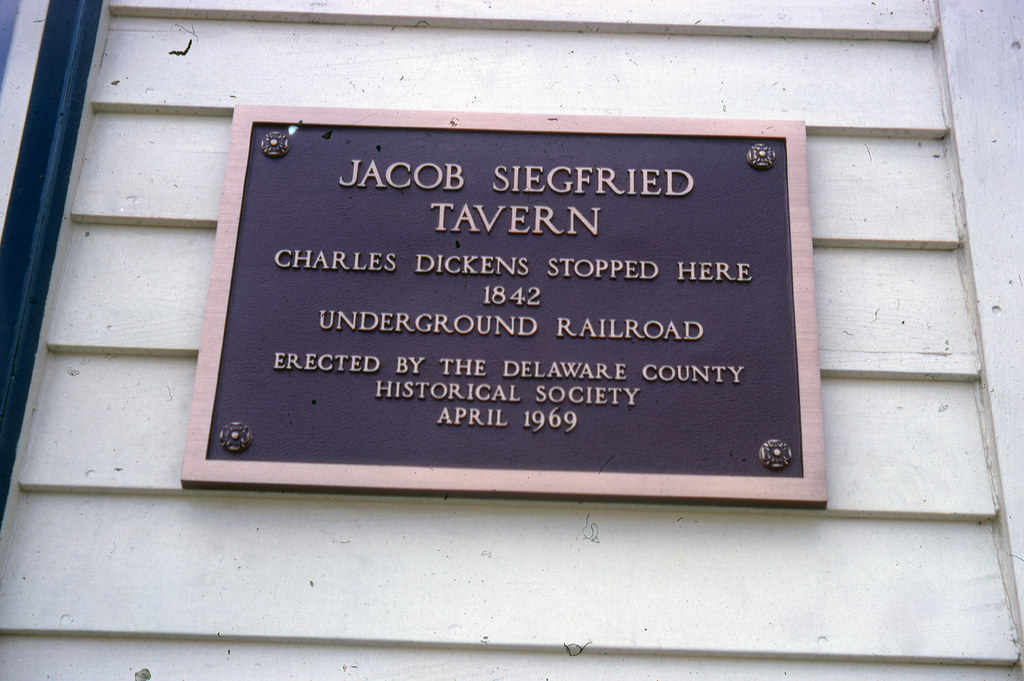

Affixed to the building is a metal plaque, rendered unreadable (during summer months, at least) by unkempt bushes. In my many years of passing the tavern, I could decipher only one word — "tavern" itself. Imagine my surprise, then, when I browsed the Delaware County Historical Society's slide collection and found this:

|

| The plaque. Image by George Cryder (?), 1969, from the Delaware County Historical Society collection. |

At first, I accepted the claim with delight. I'd long known about Dickens's 1842 excursion to America, recounted, with invaluable cynicism (1), in American Notes for General Circulation. But, after a moment's thought, I felt a twinge of uncertainty. Though I'd read (and reread) the portion of American Notes covering the Ohio leg of Dickens's journey, I could recall no mention of Delaware.

In the fourteenth chapter, Dickens describes his sole jaunt through Ohio's interior (2):

There being no stage-coach next day, upon the road we wished to take, I hired 'an extra,' at a reasonable charge to carry us [from Columbus] to Tiffin; a small town from whence there is a railroad to Sandusky. This extra was an ordinary four-horse stage-coach, such as I have described, changing horses and drivers, as the stage-coach would, but was exclusively our own for the journey. To ensure our having horses at the proper stations, and being incommoded by no strangers, the proprietors sent an agent on the box, who was to accompany us the whole way through; and thus attended, and bearing with us, besides, a hamper full of savoury cold meats, and fruit, and wine, we started off again in high spirits, at half-past six o’clock next morning, very much delighted to be by ourselves, and disposed to enjoy even the roughest journey.

We alighted in a pleasant wood towards the middle of the day, dined on a fallen tree, and leaving our best fragments with a cottager, and our worst with the pigs . . . we went forward again, gaily. (3)As I feared, not so much as a mention of inns, taverns, or Delaware. (I doubt even Dickens, contemptuous of America though he was, would dare to call Siegfried a "cottager.") In the following pages, Dickens describes only one stop between Columbus and Tiffin — Upper Sandusky, which lies well north of Delaware. If Dickens hired an "extra" for the sake of "being incommoded by no strangers," and dined (while sitting on a fallen tree) from his coach's supply of "savoury cold meats, and fruit, and wine," why would he stop at Siegfried's tavern? Why inconvenience himself with the company of strangers? And why avoid writing about the sojourn?

Dickens's diary provides few answers (though, unlike American Notes, it does mention that his coach changed horses several times). A folder labeled "Siegfried Tavern" — held by the Delaware County Historical Society — contains property research and biographical information about the Siegfried family, but barely mentions Dickens's supposed stay. The 1842 copies of Delaware newspapers seem to be lost.

The plaque's claim, then, is neither provable nor falsifiable. The weight of evidence may lie on the side of doubt, but mere weight is scarcely proof. I've no choice but to speculate.

Perhaps the story is merely hearsay — a local legend repeated by innumerable Herodotuses, and having no more credibility than the 6.2 x 10^14 similar tales about George Washington, Andrew Jackson, and Abraham Lincoln. Perhaps "Dickens passed this tavern" mutated, as verbal accounts are wont to do, into "Dickens stopped here." Or, perhaps, Dickens gave a hearty wave from his coach; Siegfried noticed and passed the impression to his descendants, in whom it transformed into today's story. Or Dickens indeed paused at Siegfried's tavern, albeit briefly, and simply for a change of horses or a bit of leg-stretching.

1) The best nineteenth-century descriptions of America tend to be those given by foreigners.

2) Though Dickens twice visited Cincinnati, he ventured into the state proper only once.

3) American Notes for General Circulation, Volume II (1842), 133–134.