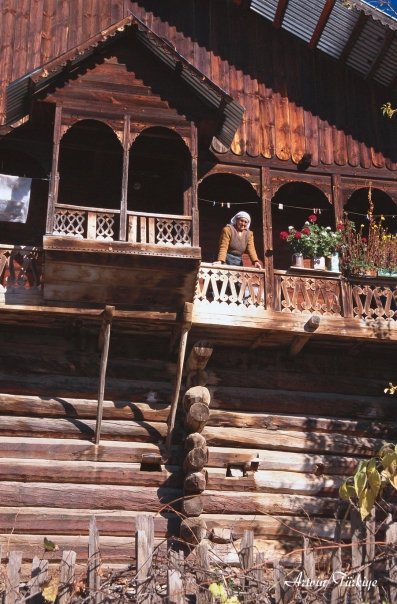

I've written a few posts about the fearsome and enigmatic Heptacometae (or

Mosynoeci), who lived along the Black Sea in today's Turkey and Georgia (and who

may be related to

Kartvelian-speaking ethnic groups). The Heptacometae constructed tall log homes, and Greek and Roman accounts of their abodes constitute the world's oldest surviving descriptions of stacked-log construction. Of these accounts, Vitruvius's — part of his

De Architectura — is certainly the finest.

Having spent a few semesters studying Latin, I thought I'd try to translate Vitruvius's text — with the help of a dictionary, of course. After all, the best way (and arguably the only

true way) to understand an author is to read

his writing. Perhaps Vitruvius himself mentions something his translators miss . . . or vice versa. Here's the Latin (from

The Latin Library):

Apud nationem Colchorum in Ponto propter silvarum abundantium arboribus perpetuis planis dextra ac sinistra in terra positis, spatio inter eas relicto quanto arborum longitudines patiuntur, conlocantur in extremis partibus earum supra alterae transversae, quae circumcludunt medium spatium habitationis. Tum insuper alternis trabibus ex quattuor partibus angulos iugumentantes et ita parietes arboribus statuentes ad perpendiculum imarum educunt ad altitudinem turres, intervallaque, quae relinquuntur propter crassitudinem materiae, schidiis et luto obstruunt. Item tecta, recidentes ad extremos transtra, traiciunt gradatim contrahentes, et ita ex quattuor partibus ad altitudinem educunt medio metas, quas fronde et luto tegentes efficiunt barbarico more testudinata turrium tecta.

After several hours of slogging, I managed to produce this:

Within the nation of Colchis, in Pontus, of abounding woods, uncut trees are put down, level, on the earth, on the right and left, with such an area left between them as the lengths of the trees allow; the others, which enclose the middle area of a dwelling, are arranged side-to-side, extending beyond the walls. Next, on top, successive trunks are fastened together at the four corners, and thus walls of trees are built up, each perpendicular to the last. The Colchians bring these up to tower-height, and the spaces, which are always left equal to the thickness of the wood, they stop up with wood-chips and mud. They place their roofs likewise, drawing them together step-by-step, the crossbeams stepping back to the walls; and thus, from the four walls, they build up their homes in the middle to the height of pyramids, which they cover with leaves and mud; and in this foreign land, by this custom, they create the vaulted roofs of their towers.

It's earthy, literal, and a bit stilted. Compare it to Joseph Gwilt's 1826

translation:

The woods of the Colchi, in Pontus, furnish such abundance of timber, that they build in the following manner. Two trees are laid level on the earth, right and left, at such distance from each other as will suit the length of the trees which are to cross and connect them. On the extreme ends of these two trees are laid two other trees transversely: the space which the house will inclose is thus marked out. The four sides being thus set out, towers are raised, whose walls consist of trees laid horizontally but kept perpendicularly over each other, the alternate layers yoking the angles. The level interstices which the thickness of the trees alternately leave, is filled in with chips and mud. On a similar principle they form their roofs, except that gradually reducing the length of the trees which traverse from angle to angle, they assume a pyramidal form. They are covered with boughs and smeared over with clay; and thus after a rude fashion of vaulting, their quadrilateral roofs are formed.

And Morris Morgan's 1914

interpretation:

Among the Colchians in Pontus, where there are forests in plenty, they lay down entire trees flat on the ground to the right and the left, leaving between them a space to suit the length of the trees, and then place above these another pair of trees, resting on the ends of the former and at right angles with them. These four trees enclose the space for the dwelling. Then upon these they place sticks of timber, one after the other on the four sides, crossing each other at the angles, and so, proceeding with their walls of trees laid perpendicularly above the lowest, they build up high towers. The interstices, which are left on account of the thickness of the building material, are stopped up with chips and mud. As for the roofs, by cutting away the ends of the crossbeams and making them converge gradually as they lay them across, they bring them up to the top from the four sides in the shape of a pyramid. They cover it with leaves and mud, and thus construct the roofs of their towers in a rude form of the 'tortoise' style.

I made no great discoveries, alas. (And interpreting

barbarico more as "in the foreign land, by this custom" — rather than "by a barbaric custom" — was probably a mistake.) Still, it's a start.

(For those interested, I created a sloppy interlinear translation, available

here.)