One of Ohio's more inventive variants of the single-pen log dwelling stood at the southern periphery of Greene County, in Caesar's Creek Township (2). The home belonged to James Frederick Hartsook (1831–1912) in the 1870s, and it stood, in almost unaltered condition, well into the 1970s. Donald Hutslar describes (and illustrates) it in his Architecture of Migration.

|

| Photo by Donald Hutslar, 1971, published in The Architecture of Migration. |

The house's distinctive features were numerous: overhanging plates, a centered second-floor tripartite window, a twelve-over-eight sash pattern, scalloped rake boards (barely visible in the photo above), a partly enclosed storage area adjoining the house proper, and, most notably, two front entries. Now, such paired doorways are a common sight in Ohio — particularly in regions settled by Pennsylvanians and Germans — but they tend not to adorn log buildings (no doubt because of the interior divisions they presuppose). As its fenestration suggests, the house was divided into two rooms, albeit not by the usual board or frame partition; instead, the builder opted for a central log wall. This wall, of course, terminated at the upper floor, just below the window. I'd love to know how the second floor was arranged, but, alas, Hutslar's description falls just short. I can say that the interior contained an enclosed staircase, placed against the central log wall. The six-panel doors are standard Federal-era fare.

Much to my surprise, researching the house's history was a breeze. An 1855 map of Greene County lists "E.B. Hartsook" as the property's owner. "E.B." was no doubt Elijah Benjamin Hartsook (1798–1863), father of James (mentioned above), who must have inherited the farm after Elijah's death. The Hartsooks hailed from Hagerstown, Maryland (though they seem to have tarried in eastern West Virginia), and their family farmhouse appears to have Mid-Atlantic antecedents. Attached to Elijah's Find A Grave page is this helpful note:

Eleazer United Methodist Church, 1765 E. Spring Valley-Paintersville Road — Elijah Hartsook bought land in Caesars Creek Township in 1834 to build a home. He donated a plot of land for the church and cemetery. The church was probably finished around 1846, at a cost of $600.This corroborates nicely with Hutslar's estimated construction date of 1833. Elijah Hartsook, then, built or commissioned the house in 1833 or 1834, in a style amenable to his central-Maryland origin. There. Simple. Case closed.

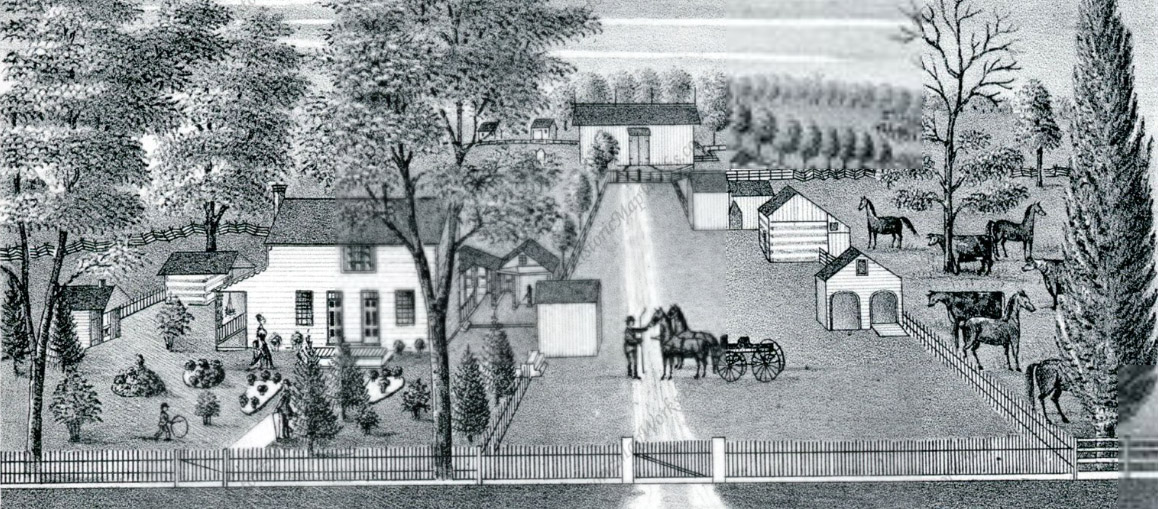

Like a few dozen other Greene County landowners, James Hartsook enjoyed the honor of his residence's inclusion in the Combination Atlas–Map of Greene County, Ohio (1874). The lithographer tasked with capturing the Hartsook farm's likeness did much justice to reality (and equal injustice to perspective). The illustration faithfully reproduces all that made Hartsook's abode distinctive: its second-floor window, its overhanging plates, and even its scalloped trim.

This raises an interesting point. Instinct and cynicism inform me that I ought to treat such illustrations with skepticism. After all, citizens paid for these engravings, and what homeowner wouldn't forgive a bit of artistic license, provided that it flattered him? Evidence and experience, though, suggest that the hundreds of illustrations adorning Ohio's nineteenth-century atlases are, for the most part, accurate depictions of reality. And we architectural historians ought to study them.

1) Does the rule that every rule has an exception itself have an exception?

2) No other Ohio township name is so inconsistently spelled. Some nineteenth- and twentieth-century documents use Caesar Creek (without a possessive), whereas others add that lovely English vestigial genitive, but omit the conventional apostrophe (making Caesars Creek). Wikipedia smashes together the two words in horrifying (but oddly trendy) fashion — hence Caesarscreek. (Gesundheit!) I'd throw my support behind the one variant that seems not to appear in print: Caesar's Creek.

No comments:

Post a Comment